This Landscape Resilience project built on the successes of previous Landscape Resilience projects (2013-2016 and 2016-2017).

Since 2013, these projects have provided 69 cane farmers in the Lower Burdekin with individualised, real-time irrigation runoff data, which can support them to improve their farming practices. These projects have informed participants and the wider community about the importance of wetlands, and the connectivity between farms, wetlands, and downstream environments, including the Great Barrier Reef (GBR).

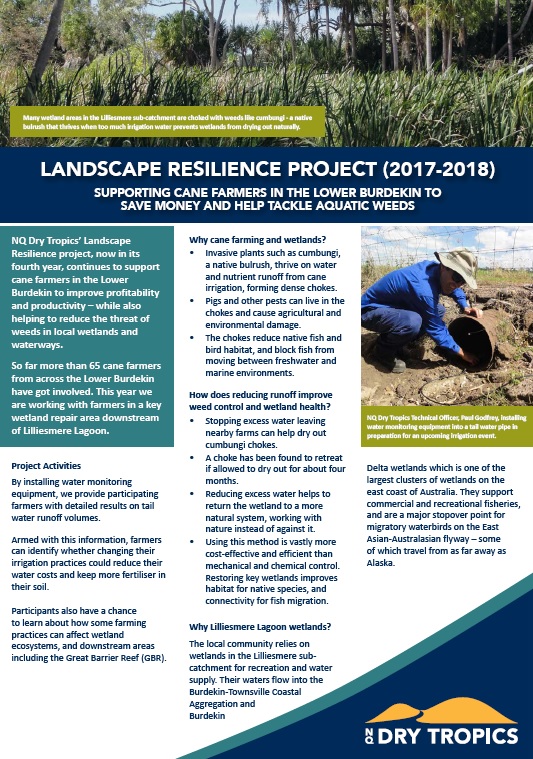

The 2016 – 2017 project was located in a key wetland area downstream of Lilliesmere Lagoon. NQ Dry Tropics project officers engaged with three cane farmers and measured tail water runoff during irrigation events. This data was provided to each farmer along with an explanation of what it means.

Why cane farming and wetlands?

Cumbungi, a native bullrush, thrives on abundant water and nutrients from cane irrigation and forms dense chokes that:

- provide habitat for pigs and coots, which damage agriculture and the environment;

- reduce the ability of the shallow coastal wetlands to trap sediment, nutrients and other pollutants before they reach the coast;

- reduce habitat for native fish and birds; and

- prevent fish from moving between freshwater and marine environments.

How does reducing runoff improve weed control and wetland health?

- Stopping excess water leaving nearby farms can help dry out cumbungi chokes.

- A choke has been found to retreat if allowed to dry out for about four months.

- Reducing excess water helps to return the wetland to a more natural system, working with nature instead of against it.

- Using this method is vastly more cost-effective and efficient than mechanical and chemical control.

- Restoring key wetlands improves habitat for native species and connectivity for fish migration.

What has it got to do with the Reef?

- The Burdekin Water Quality Improvement Plan (WQIP) found that the most cost-effective and efficient way to reduce nitrogen run-off to the Reef is by improving farm irrigation.

- Improving coastal wetlands can also help improve the quality of water leaving the land.

- The GBR also includes near shore environments such as mangroves where barra, mangrove jack, prawns, and crabs spend part of their life cycles; and seagrass meadows, which provide habitat and feeding grounds for dugongs and marine turtles.

Did you know?

The Lilliesmere sub-catchment wetlands are very important freshwater lagoons valued by the local community for recreation, water supply, and as waterbird and fish habitat. Part of the Lower Burdekin Water irrigation delivery area, they flow into Upstart Bay and the GBR.

These wetlands also provide support areas for the internationally-listed Ramsar wetlands of Bowling Green Bay and the nationally-important Burdekin-Townsville Coastal Aggregation and Burdekin Delta wetlands. One of the largest clusters of wetlands on the east coast of Australia, the Burdekin-Townsville Coastal Aggregation supports commercial and recreational fisheries, hosts significant breeding populations of waterbirds, and provides a major stopover point for migratory waterbirds on the East Asian-Australasian flyway – some coming from as far away as Alaska.

The Landscape Resilience project (“Improving Coastal Wetland Ecosystems through improved understanding of Best Irrigation Management Practice in the Lower Burdekin”) is delivered by NQ Tropics and funded by the Queensland Natural Resource Investment Program.