Close the gate, then open a new paddock and a new life

As one farm gate closes, another opens.

Manager of Lamington Park for more than a decade, Sam and wife Genevieve Clarke are moving onto bigger and better things… almost 50 times bigger at a beef cattle stud near Eidsvold.

Sam has been appointed Livestock Manager of Eidsvold Station, the oldest Santa Gertrudis Stud in Australia. At 20,000ha, it’s a big responsibility, but one that he is itching to get his teeth into.

The Clarkes left Lamington Park proud of the legacy of their work evident in the sleek cattle happily grazing lush, green paddocks.

When Sam assumed management of the 440ha (1080acres) property more than a decade ago, it was, in his words, “a bit of a desert”.

“We were flat out running a beast for every 12 acres (5ha),” he said.

They could support 100 head from the family’s breeding property Brinawa near Burketown, and no more.

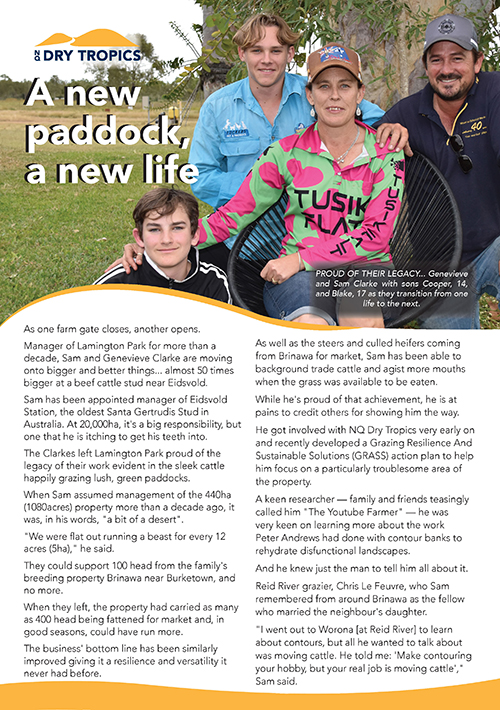

MOVING DAY… the Clarke family on the day they closed the gate on Lamington Park and prepared to tackle their new life: Genevieve and Sam with sons Cooper, 14, and Blake, 17

Click to download a PDF of the case study.

The Saltflat paddock at Lamington Park, the most difficult piece of country to rehabilitate. It was the focus of the property’s GRASS Action Plan. This photograph was taken in April, 2021. HOVER the mouse above the image to see the same paddock (albeit from the opposite end) in May, 2023. Move the mouse on and off the image to compare the two.

When they left, the property had carried as many as 400 head being fattened for market and, in good seasons, could have run more.

The business’ bottom line has been similarly improved giving it a resilience and versatility it never had before.

As well as the steers and culled heifers coming from Brinawa for market, Sam has been able to background trade cattle and agist more mouths when the grass was available to be eaten.

While he’s proud of that achievement, he is at pains to credit others for showing him the way.

He got involved with NQ Dry Tropics very early on and recently developed a Grazing Resilience And Sustainable Solutions (GRASS) action plan to help him focus on a particularly troublesome area of the property.

A keen researcher — family and friends teasingly called him “The Youtube Farmer” — he was very keen on learning more about the work Peter Andrews had done with contour banks to rehydrate disfunctional landscapes.

And he knew just the man to tell him all about it.

Reid River grazier, Chris Le Feuvre, who Sam remembered from around Brinawa as the fellow who married the neighbour’s daughter.

“I went out to Worona [at Reid River] to learn about contours, but all he wanted to talk about was moving cattle. He told me: ‘Make contouring your hobby, but your real job is moving cattle’,” Sam said.

Sam and Genevieve were convinced and embraced the idea enthusiastically.

They developed a system of grazing paddocks in “daily bites” using temporary electric fencing to restrict a small mob (100-250 beasts) to a day’s worth of pasture.

Every day at about 3pm, they would move the mob onto the next strip of grass, then, when the cattled were settled, remove the fence on the watering point side of the strip.

With Sam away at the Burketown property for almost six months of the year, it fell to Genevieve and sons Blake and Cooper to maintain the intense system.

While it did have the desired effect — the cattle ate everything, weeds and all, became much quieter because they had human contact every day and the pasture responded, growing back thicker and better after each graze — it was too labour-intensive to be sustainable.

“I learnt that you could get the same result by keeping them in a slightly bigger area for up to seven days, depending on all the variables like weather, soil type, pasture and so on,” he said.

“After about seven days, the best grass, which had been grazed first, starts to grow back, so I always want to get the cattle off that to give it a chance to grow properly. All the time they’re in that paddock, they’re adding dung and urine and churning up the soil with their hooves. It all helps.”

Sam said by identifying degraded areas on a property and prioritising them, it was easy to see how they could be improved by moving cattle.

The GRASS action plan made it easy to prioritise and implement decisions and to keep the records necessary to meet reef protection regulations.

He said he would definitely look at a GRASS action plan in his new role if one wasn’t there already.

And he will be keen to implement the grazing systems he developed at Lamington Park.

“Really, it’s about affecting the paddock by grazing it, then resting it,” Sam said.

“It’s that simple.”

He said the skill was in knowing the degree to which a paddock should be affected, then rested.

“The more you do it, the better you get,” he said.

He and Genevieve have been open to other ideas as well. They experimented with a no-till planter spreading seca, bluegrass, rhodes, panic, urochloa, coastal Flinders, sorghum, sunflowers and other native flowers to try to kickstart some bare areas.

It worked, but the real difference was made when he was able to bring in the cattle to do their work.

Sam Clarke (right) listens to David Marsh explaining minimal input natural grazing.

What a difference a decade makes… now there is nowhere on Lamington Park Station that bears any resemblance to this landscape.

Genevieve Clarke with favourite dog, Dexter at a working dog school.

With Sam away for long periods, they were always on the lookout for easier ways to manage cattle and for help making those regular moves.

Sam’s uncle, Percy Clarke, gave them the answer.

A working dog enthusiast, he told them about the benefits of using dogs to work cattle.

“Dogs calm the cattle,” Sam said.

“Frequent moves help to make the cattle less worried about coming near humans but when you use dogs to move them, they really become quite calm and work together.”

They now have a small pack of seven working dogs and they’re regulars at workshops and schools involving working dogs.

The couple were recently members of an NQ Dry Tropics five-day tour of Mulloon Institute farms and nearby properties.

For Sam and Genevieve, it was more confirmation that they were on the right track with their efforts at Lamington Park.

“We achieved a fair bit in five years, but it was good to see what can be accomplished in the longer term,” Sam said.

“It was great to see how they were driving soil structure and soil carbon.

“That’s what I want to do always.”

The GRASS program is funded through the Queensland Government’s Queensland Reef Water Quality Program and is delivered by the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries and NQ Dry Tropics.

A small pack of working dogs helped make regular cattle moves an easy task.